Feb 22, 2026

Stani Kulechov argues DeFi should finance $30–50 trillion in abundance assets. He’s right about the opportunity. But pools are the wrong tool for the job.

Stani Kulechov recently published Funding Abundance, a sweeping thesis that DeFi should become the financing layer for the world’s transition to energy abundance: solar, batteries, robotics, vertical farming, semiconductors. He envisions $30–50 trillion in tokenized “abundance assets” flowing onchain by 2050, with DeFi protocols replacing traditional infrastructure finance.

The vision is compelling. The macro case is airtight. Solar investment alone needs to reach $600 billion to $1 trillion annually to hit net zero. There are $25 billion in real-world assets already tokenized onchain, and the number is accelerating. The capital is hungry. The collateral is coming.

But here’s the question nobody is asking: is the current DeFi lending architecture actually built to serve this market?

We don’t think so. And we think the answer matters more than the opportunity itself.

The Pool Problem

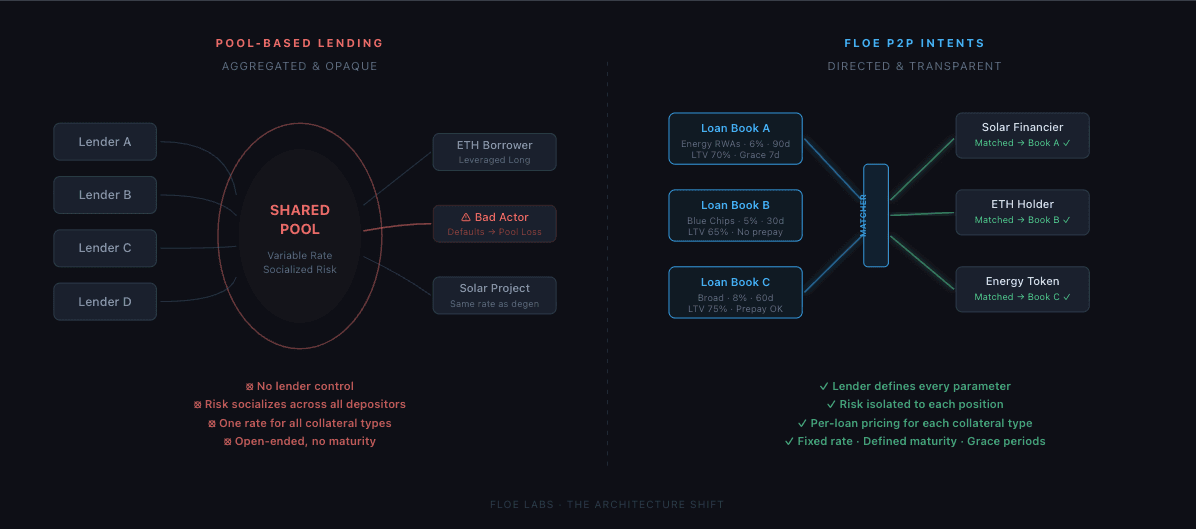

Pool-based lending protocols were a necessary innovation. In 2017, the infrastructure for true peer-to-peer matching didn’t exist. Oracles were immature, L2s hadn’t launched, keeper networks were unreliable, and transaction costs made individual loan matching impractical. Pools solved the cold-start problem by aggregating all supply and all demand into a single shared bucket.

That design works when collateral is homogeneous. ETH is ETH. USDC is USDC. A utilization curve can price the whole pool because every unit of collateral is functionally identical.

Abundance assets are the opposite. A tokenized solar farm in Texas has different risk than one in Morocco. A 30-day loan against crude oil-backed tokens at 60% LTV is a fundamentally different product than a 180-day loan against the same asset at 75% LTV. Senior debt on a $100 million solar project with a 20-year PPA from a utility is not the same as equity in a pre-revenue battery storage startup.

Pools can’t distinguish any of these. Every deposit enters the same bucket. Every depositor earns the same rate. Every borrower faces the same utilization-driven variable rate that can swing 100%+ in a single block. Risk is socialized. Pricing is averaged. Lenders have zero control over what their capital funds.

Stani himself has pointed out that vault curators in the current system are “conflicted, taking excess risks to compete.” This isn’t a people problem. It’s a structural incentive: in a shared pool, there’s no economic reward for being conservative. A curator running a 50% LTV strategy earns the same utilization-curve rate as one pushing 85%. The architecture can’t compensate caution.

The core issue: Abundance assets are heterogeneous. Pools are homogeneous. You can’t price a $15–50 trillion market of diverse real-world infrastructure with a single utilization curve.

What Structured Credit Actually Requires

Traditional infrastructure finance doesn’t use pools. A bank lending against a solar project underwrites that specific project—its PPA terms, offtaker creditworthiness, geographic risk, degradation curve, insurance coverage. The loan has a fixed rate, a defined maturity, negotiated covenants, and a repayment schedule. The lender chose this exact exposure because it matches their risk appetite.

If we’re serious about onchain lending absorbing trillions in real-world infrastructure debt, the protocol architecture needs to support how credit actually works:

Requirement | Pool Model | Floe |

|---|---|---|

Directed capital |

|

|

Fixed rates |

|

|

Term structure |

|

|

Risk isolation |

|

|

Per-loan pricing |

|

|

Lender loan programs |

|

|

Transparency |

|

|

This isn’t a feature comparison. It’s an architectural divergence. The question isn’t which protocol has better UX—it’s which model can serve a market where every piece of collateral is unique and every lender has a specific risk mandate.

Loan Books, Not Deposits

Here’s where the design gets concrete.

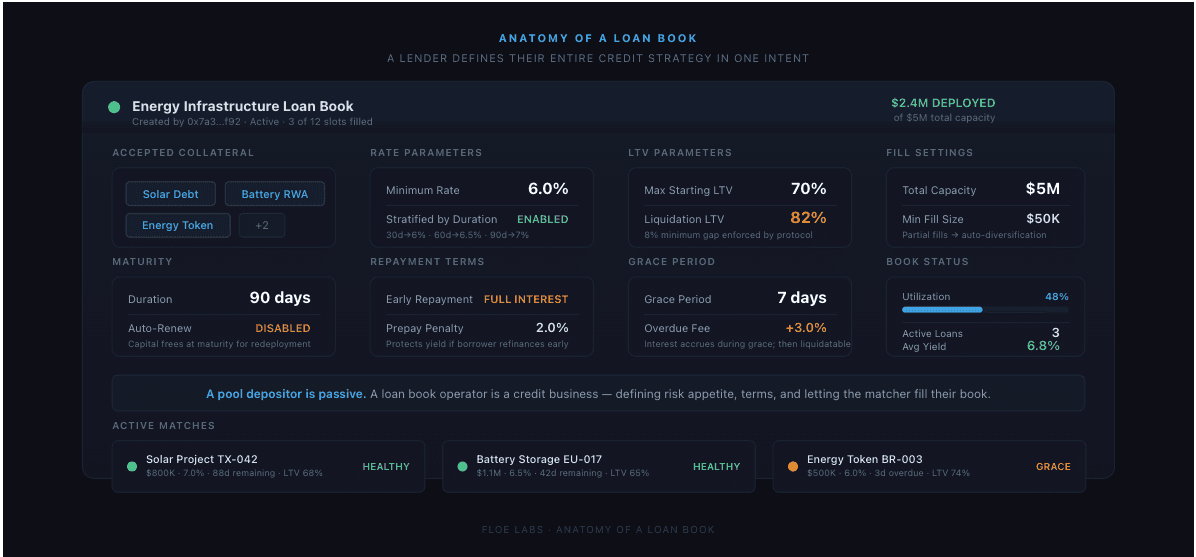

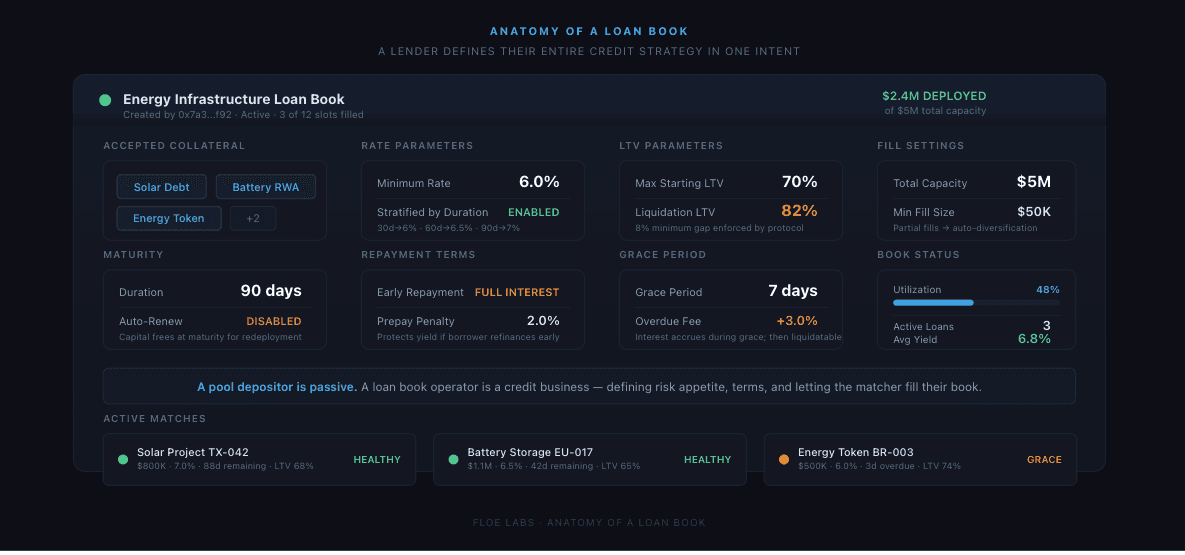

On Floe, a lender doesn’t “deposit into a pool.” A lender creates a loan book: a structured set of terms that defines exactly how their capital should be deployed. This is a fundamentally different primitive.

A loan book on Floe includes:

Accepted collateral. Which asset types the lender will lend against. Today that’s ETH, BTC. Tomorrow it’s tokenized solar debt, energy commodity tokens, private credit instruments. The lender chooses.

Rate floor. The minimum interest rate the lender will accept. No utilization curve surprises. The rate locks at match time and never changes for the life of the loan.

LTV parameters. The lender sets their liquidation threshold. A conservative lender can run 50% LTV and get compensated for that conservatism through the rate they demand. An aggressive lender can push higher. The market prices the difference; not the protocol.

Maturity and repayment structure. This is new, and it’s what makes Floe feel like real credit infrastructure. Lenders set defined maturities—not open-ended positions. They configure grace periods for overdue loans, during which interest continues to accrue. They set minimum equity multiples, minimum interest and prepayment terms: allow early repayment, disallow it entirely, or require borrowers to pay full interest owed over the life of the loan to exit early. They define overdue fees. These are the mechanics of structured credit—the same tools that a solar project financier, an energy commodity lender, or an institutional credit desk expects to work with.

Multiple borrowers. A single loan book can match against multiple borrowers over time, each creating a separate, isolated loan. One lender intent diversifies across different borrowers, durations, and risk profiles automatically.

The mental model shift: A pool depositor is passive. A loan book operator is a credit business. They define their risk appetite, set their terms, and the protocol’s matching engine fills their book with compatible borrowers. This is how lending scales for heterogeneous collateral.

Why This Matters for Abundance Assets

Stani’s abundance thesis describes a world where a solar debt financier tokenizes a $100 million project and borrows $70 million against it in stablecoins, redeploying immediately into new builds. Depositors earn “enormously scalable, low-risk yield that is well diversified.”

Walk through that scenario on each architecture:

In a pool

The $100 million in tokenized solar debt enters a shared collateral pool. The financier borrows at a variable rate determined by total pool utilization—a rate that has nothing to do with the quality of their solar project. Depositors earn yield but have no idea their capital is funding a solar farm versus a leveraged crypto position. If a different borrower in the pool defaults on an unrelated position, bad debt socializes. The solar financier’s loan is contaminated by risks they never agreed to.

On Floe

The financier posts their tokenized solar debt as collateral and sets their terms: $70 million borrow, 70% LTV, 90-day maturity, willing to pay up to 7% fixed. A lender operating an energy-focused loan book matches against it. The lender chose this exposure because they evaluated the PPA, the offtaker, the jurisdiction. The rate locks. The maturity is defined. If the loan goes bad, the loss is isolated to that position. No contagion. No surprises.

The lender can require full interest payment on early repayment—protecting their yield if the financier refinances. They can set a grace period so a temporarily overdue position accrues penalty interest rather than immediately liquidating, which makes sense for real-world assets where cash flows arrive on schedules, not in real-time. These are the tools that make institutional capital comfortable lending against infrastructure.

Now multiply this by thousands of solar projects, battery installations, and energy commodity positions across dozens of jurisdictions. Each one is different. Each one needs individual pricing. Each lender has a different risk mandate. This is a matching problem, not a pooling problem.

The Capital Recycling Advantage

Stani makes an underappreciated point about capital velocity: “Traditional infrastructure capital locks up for decades. Tokenized assets allow continuous trading, meaning the same dollar can finance multiple projects over time.”

Floe's P2P intent matching with defined maturities takes this further. In a pool, capital sits at whatever utilization rate the market dictates. There’s no mechanism to ensure your capital is continuously deployed at terms required.

On Floe, a loan book with a 90-day maturity automatically frees capital at expiration. The lender can immediately redeploy a new loan book or into the next matching intent. A lender can run overlapping loan programs with staggered maturities—30, 60, 90 days—creating a rolling credit facility that continuously recycles capital into new projects. The same dollar finances more infrastructure per year because deployment is directed, not passive.

This is how traditional credit desks operate. They manage a book with defined maturities, reinvestment schedules, and risk budgets. Floe brings that operational model onchain.

Multi-Currency and the Stablecoin Demand Problem

Stani identifies a persistent chicken-and-egg problem: non-USD stablecoins (EUR, GBP) lack demand-side use cases onchain, so they never achieve critical mass. His proposed solution is that globally distributed solar farms create natural demand for local currency borrowing.

Directed P2P matching solves this more cleanly than pools. A European solar developer tokenizes EUR-denominated senior debt, posts it as collateral on Floe, and sets a borrowing intent for EUR stablecoins. A European lender operating a EUR-denominated loan book matches against it. The yield is in EUR, backed by local infrastructure, with transparent per-loan risk.

In a pool model, EUR stablecoins from all depositors would be aggregated together, lent against mixed collateral, at a single utilization-driven rate. There’s no way for a EUR depositor to say “I only want exposure to European solar infrastructure at 6% minimum yield.” On Floe, that’s the default behavior.

The Synthesis

The pool was a stepping stone. It proved that DeFi lending could aggregate global capital at scale. That problem is solved.

The next problem is the demand side in bringing new collateral onchain that absorbs hungry capital into real financial opportunities. Stani is right: abundance assets are the answer. Solar alone is a $10–50 trillion opportunity. Energy commodities, batteries, robotics, and the rest expand it further.

But the protocol architecture that solved capital aggregation is not the architecture that solves capital allocation. Aggregation is a pooling problem. Allocation is a matching problem. Homogeneous assets need pools. Heterogeneous assets need loan books, fixed terms, defined maturities, directed capital, and isolated risk.

The infrastructure for true peer-to-peer matching now exists. L2s with sub-cent transactions. Robust oracle networks. Automated keeper infrastructure. AI agents that can translate “lend $500K against tokenized solar at 6% for 90 days” into programmable credit.

The future of DeFi lending isn’t bigger pools. It’s better credit.